When you look at Arsène Wenger what do you see? A shining light for longevity, the last of his kind overseeing a period of time at one club, something that is now unique? A 66-year-old manager who seems past it, his methods overtaken by younger, hungrier, craftier coaches? A stubborn man? A loyal man? A romantic? A revolutionary? A relic? A survivor?

It explains a lot about him, and how he is perceived, that after an extraordinary 20 years at Arsenal, he can be all of them. Here we chronicle the seven ages of his time at the club.

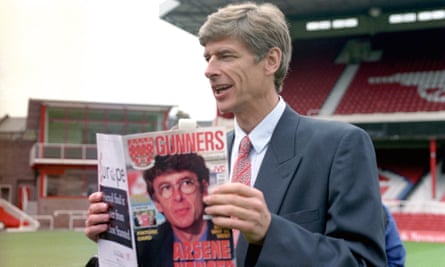

Brave New World (1996)

Nobody, least of all the man himself, envisaged the depth of the opportunity ahead when Wenger weighed up the prospect of joining Arsenal in 1996. He gave the offer careful thought in his apartment in Nagoya, where he was living while manager of Grampus Eight. His spell in Japan provided an experience that fascinated him. Far away from the madding crowd of European football, he immersed himself in a culture and in a way of life that was by its nature challenging, engaging, eye-opening, and at times lonely. The work was stimulating. But friends, family and familiarity were almost 10,000km away.

The Arsenal opening represented a mighty leap in every way – professionally, culturally, personally. “I was at a dangerous point and I had to make a decision. I felt that if I didn’t come back now I would stay forever in Japan,” he explained. “After two years you get slowly emerged into this spirit. What you miss in Europe is slowly drifting away. I was at a point where I thought, I will make my life here if I don’t come back now.” His wife was pregnant with their daughter. Either they would make the big move to Japan to join him and Wenger would commit to deepening his roots in Asia, or he would return to Europe. In hindsight, this was a sliding doors moment. Who knows how his subsequent decades – and Arsenal’s – would have turned out had he taken the other decision?

Half a world away in London, his friend, the then Arsenal vice-chairman David Dein, awaited Wenger’s choice. From their first chance meeting in 1989, when Wenger was passing through London with some time to kill on the day of a north London derby, Dein had been wowed by this individual who struck him as completely different to the average manager. He first proposed the idea of appointing this clever, worldly Frenchman working in the J-League in 1995, only for his fellow board members to reject it as far too risky. A foreign manager? What an audacious suggestion. There was no evidence to suggest it would work at all.

There had been only one experiment with a manager from abroad in the top flight before. Aston Villa hired Dr Josef Venglos (predictably welcomed as “Dr Who?”) in 1990. He arrived fresh from coaching Czechoslovakia at the World Cup, a multi-linguist who could communicate in Russian, Portuguese, Spanish and English as well as his native tongue. But a lot was lost in translation and Venglos left after one troubled season narrowly avoiding relegation. Venglos tried to introduce ideas relating to what he called: “The methodology of training, the analysis of nutrition, recuperation, regeneration and a physiological approach to the game.” Frankly, most of those words sounded like they came from outer space to your average 1990 English dressing room.

We now live in an age when the currency of overseas managers in the Premier League has never been higher. With the richly decorated backstories of Pep Guardiola and José Mourinho dominating the Manchester scene, Jürgen Klopp reigniting soul in Liverpool, the fiercely competitive Italian Antonio Conte tasked with whipping Chelsea into shape, Ronald Koeman and Mauricio Pochettino bringing elements of the Dutch and Argentinian schools to Everton and Tottenham in the chasing pack, we are familiar with all accents, philosophies, tactical preferences, foibles.

When Wenger arrived with his French lilt and sophisticated ideas he came into an environment with a deep mistrust when it came to the possibility that a foreigner could succeed in England. If Tony Adams, Arsenal’s influential captain, felt unsure, then so would everybody else. “There was a fear of someone else, a fear of change,” Adams remembered, later describing the mood succinctly as “contempt before investigation”. The general reaction from players, managers, supporters and media across England was pocked with suspicion.

Wenger was conscious of it. “I felt quite a lot of scepticism,” he said. “That’s normal, especially on an island. This phenomenon is more emphasised on an island because people have historically lived more isolated. They are more cautious about foreign influences.”

22 September 1996. When Wenger made his first public appearance as Arsenal’s new manager, sporting a gaudy club tie and dark blazer, with a press conference at Highbury to formally introduce himself before properly starting work on 1 October, nobody knew quite what to expect. The only other foreign coach working in England had only just been promoted – Ruud Gullit took over from Glenn Hoddle to become Chelsea’s player-manager during the summer. After “Dr Who?” came “Arsène Who?” Unlike Gullit, who had a global reputation and was already a familiar face in Premier League football when he was appointed to the Stamford Bridge dugout, Wenger was a virtual unknown.

Have a look at the list of managers who began the 1996-97 Premier League season:

Brian Little (Aston Villa), Ray Harford (Blackburn), Gullit (Chelsea), Ron Atkinson (Coventry), Jim Smith (Derby), Joe Royle (Everton), George Graham (Leeds United), Martin O’Neill (Leicester) Roy Evans (Liverpool), Alex Ferguson (Manchester United), Bryan Robson (Middlesbrough), Kevin Keegan (Newcastle), Frank Clark (Nottingham Forest), David Pleat (Sheffield Wednesday), Graeme Souness (Southampton), Peter Reid (Sunderland), Gerry Francis (Tottenham), Harry Redknapp (West Ham), Joe Kinnear (Wimbledon).

Old school, to say the least. Not the platform for the most open or warm of welcomes.

Pass With Flying Colours (1996-1998)

It was Patrick Vieira who started the ball rolling. This rangy and athletic young midfielder – another Frenchman few in England knew anything about – was signed all of a sudden from Milan and represented a sort of advanced party before Wenger was freed from his commitments in Japan to start work with Arsenal. Actually it was more of an advanced present. Vieira made his debut midway through the first half of a modest performance against Sheffield Wednesday at Highbury under the caretaker control of Pat Rice. He came on and it was a shining lightbulb moment. Dennis Bergkamp, who was injured and watching from the sidelines, felt the crackling energy sweeping through dear old Highbury. “When he came on he changed the game. He completely changed the game!” the Dutchman recalls. “And I think everyone in the stadium was thinking, ‘What happened here? Did I really see it right?’”

Having been pedestrian and workmanlike in midfield for a few years – it certainly wasn’t the team’s most refined department – Vieira’s appearance made a vital impression. He represented something fresh and different. As Wenger said: “He is the man who gave me the first credibility. It was a shock to people. He was like a genie from the lamp.”

Although life at Arsenal was about to change radically, Wenger did not want to be too judgmental or impose too much of a revolution without taking his time to look around and assess everybody.

1 October 1996. Wenger’s first official day at work was spent at the training ground. Over the next two seasons he would introduce a range of new ideas. Some were based on science – everything from discouraging chocolate bars on the team coach, revising dietary habits and liquid intake (not only what you ate and drank but how you took it on board) and introducing stretching regimes and fitness specialists. Some were based on style of play, and short to-the-point training sessions designed to create the template for football that was both powerful and expressive. A knack for signing perfect players to fit the new jigsaw helped. In came quality of the calibre of Marc Overmars and Nicolas Anelka, whose pace frightened the life out of opposition defenders, and Emmanuel Petit, whose defensive instincts and long passes made him the ideal midfield foil for Vieira. All these ingredients whirled together to create a winning blend.

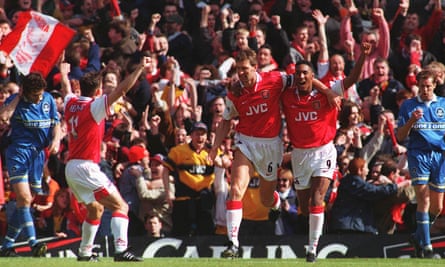

For Bergkamp, the arrival of Wenger built a bridge between the football of his past, his education in the Dutch ideals of total football, and the never-say-die English football attitudes that were embodied by Arsenal’s steely back four. There was a kind of symbiosis. Consider how Bergkamp absorbed the toughness which helped him to electrify the Premier League, or how Adams had the freedom to burst on to a chipped pass from Steve Bould to score with an impeccable volley.

It all came together beautifully in Wenger’s first full season as Arsenal won the Premier League and FA Cup double. There was something almost serene about how his team glided towards the honours at the end of the season. Wenger is acutely aware of the manifold complications football throws up, but just sometimes, and the finale to the 1997-98 double was one of those times, he has been able to experience the rare glow that transcends all the pressures. “Of course. It happens when you feel your team is a really happy unit playing the game and enjoying it. Not distracted by any selfishness or any anxiety about the result. It’s like you lead 3-0, everybody is up behind the team, they express themselves, they still respect the game. That’s it. It sometimes lasts three, two, or one minute. It’s so short, but you would battle forever to experience that again.”

The Wonder Years (1998-2006)

Wenger’s first decade yielded convincing, regular success. It was not without its towering disappointments. In between the doubles of 1998 and 2002 were three frustrating seasons of being close but not winning. They were league runners-up each season behind domestic rivals Manchester United, and also lost a bunch of painful semi-finals and finals. The rivalry with Alex Ferguson’s team was intense and compelling.

But overall, during the period between 1996 and 2006, Arsenal won the Premier League three times, FA Cup four times, reached the Champions League final for the first time in their history and went through the 2003-04 league campaign undefeated. It was an era to bear comparison with the dominance masterminded by Herbert Chapman in the 1930s.

A decade of high achievement is what the subsequent Wenger years are inevitably measured against. Recall of that time is important not only for the substance but also the aesthetic style. A team that had Thierry Henry in his prime leading the charge, with the artistry espoused by Bergkamp, Robert Pirès, Freddie Ljungberg, Vieira, Kanu and company buzzing around the pitch (not to forget a toughened defence that took every goal conceded as an affront), won many admirers.

Although he is not a man who naturally enjoys looking back, making history with the “Invincibles”, the team that didn’t lose a single league game, is a highlight that meant a great deal to him personally. “It was one of my dreams,” he said. “I learned that you can achieve things that you think are not achievable.”

Wenger’s time at Arsenal has coincided with the globalisation of the game, and creating an imprint, an identity – one that was in opposition to the “Boring Arsenal” tag they had carried for years – is something he is quietly proud of. “Sometimes when I speak to foreign coaches and ask about a player and they say, ‘This is not an Arsenal player’ this is the biggest compliment you can get,” Wenger said.

Of course, in the process of 20 years not every transfer ended up in that this-is-an-Arsenal-player bracket. On the one hand Sol Campbell, on the other Igors Stepanovs. One hand Robin van Persie, the other Francis Jeffers. But Wenger got more than enough right in that opening decade to be brilliantly successful. It was a heck of a benchmark to live up to.

Men Against Boys (2006-2013)

Coincidentally or not, in splitting the Wenger years into two contrasting halves, the mid-point is the significant moment Arsenal relocated. Wenger loved Highbury. Even now, sometimes, this man who does not easily give in to the sentimental makes a diversion when he is driving to or from the Emirates and stops outside the old East Stand facade on Avenell Road to remember.

But moving always felt, to him, imperative for the club to push forward. Having revolutionised the training facilities first of all by planning for a modern headquarters to be built (he went every day to the site at London Colney to check on the progress and is particularly fond of the fact they planted 280,500 trees), the complex question of Highbury’s small capacity required considerable thought.

When Arsenal decided to leave their ancestral home and prepare for a move that would in the end cost around £400m, Wenger knew and accepted that for a time it would compromise his team. What he did not know was that all Arsenal’s plans would be thrown by the impact of oligarchs and billionaires landing suddenly to transform the football landscape. Arsenal’s belt-tightening coincided with lavish spending elsewhere. “You feel like you have stones against machine guns,” Wenger said. “People don’t want to know that. They just want you to win the championship.” That period turned out to be more challenging than the club ever anticipated.

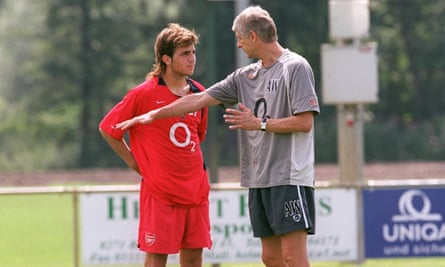

Wenger’s plan to sail the choppy waters with a modestly priced boat compared to the Premier League’s financial powerhouses was to pin his faith on youth. The idea was brave: find the best young players you can, inculcate them with some club spirit, and develop a team that grows together and feels loyalty to one another and the cause.

It nearly worked. Cesc Fàbregas in his youth was sensational. In the group that included Van Persie, Samir Nasri and Abou Diaby, Wenger was sure he had enough talent to compete.

But project youth crumbled. It was perhaps the lowest blow for Wenger. The damage when Fàbregas and Nasri left, followed by Van Persie, was felt keenly. Wenger felt a very personal sense of loss. The ideology he believed in collapsed around him. Just before the stream of high-profile departures, while he fought to stem the tide, he admitted that the message it would send if they left was too great. “You cannot pretend you are a big club,” he said.

It was hard to take, particularly for someone who likes to manage with a strong emphasis on the human side of his players. Although it hurt, and other managers may well have been more ruthless in blocking moves, rightly or wrongly Wenger always tried to recognise that if a player wanted to go, it was time to let them go.

The vulnerabilities in his team during these moments made it so tough to compete with the best around. The soft centre, the free-form style that on a bad day fell foul of well-organised opponents, the one or two elite players short they usually found themselves. Wenger bore the brunt of all the problems.

A Second Coming (2014-15)

How is your glass – half-full or half- empty? Depending on your perspective, the difficult, trophyless years provoked mockery and scorn or a quiet respect for the bigger picture. Several times during his Arsenal tenure Wenger could have left for other clubs. He never did. He stayed put, earning a handsome salary but also absorbing the flak. Why? Because he believes in an idea that is about more than honours for the CV. He started the project to see Arsenal over their expensive move, and he wanted to finish it. Whether he will or not is a question that frequently causes ripples in the fanbase. Is he the man to take the club back to the position they were in during the first decade of Wengerian Arsenal? Can he ever get them back to title-winning standards? There have been occasional close attempts, but no bullseye.

After winning the FA Cup in 2005, the last honour of part one of his tenure, Wenger endured moments of immense pressure and blame. The 8-2 defeat at Manchester United in August 2011 was deeply humiliating. There were a cluster of those calamities in recent seasons, piercingly bad defeats that allowed Mourinho to deliver that cutting “specialist in failure” line.

“The immense importance of football is sometimes scary,” Wenger said in his early days at Arsenal, admitting how it can be overwhelming to carry the burden of expectancy for a big club. “When you don’t win you are responsible for so many unhappy people. Sometimes it’s better not to think about it because it could damage your life too much.

“It’s the only way to survive. I don’t go out at all. I stay at home and try to do my best for the club. But of course in bad moments, when you play away and you lose and you see after the game all those fans who travelled for 500 miles or 1,000 miles in Europe, and spend a lot of money, you feel that atmosphere. There is a strange vibration in the street when you lose at home. You feel responsible. But you cannot survive if you only feel that – you’ll kill yourself. The professional aspect always takes over. ‘Why did we lose? What did I do wrong?’ But you can’t just wipe out those moments.”

Set against that analysis, it was meaningful when Wenger finally experienced the relief of winning again. The FA Cup final in 2014 against Hull City was a rollercoaster. Going 2-0 down was, he said, “surreal” because the thought of losing when carrying so much expectation was unthinkable. Arsenal rallied and won the Cup 3-2 in extra time. “Winning was an important moment in the life of the team. When it comes after a long time it sometimes comes with suffering,” Wenger said. “We had such a feeling of relief and happiness.” The following year they retained the trophy with a swashbuckling performance.

The graph was back on an upward curve. Silverware, and the ability to attract a higher calibre of player made a difference. When Wenger recruited Mesut Özil and Alexis Sánchez, signings that were out of their league in the drifting years, it was like suddenly buying a Porsche. Wenger felt bullish again.

The Great Survivor (2015-16)

Spooling back 20 years, remembering the man who arrived confident in his ability to make a success of this opportunity, Wenger initially thought he would take on this job for maybe three years, four or five if things went well. Now it is September 2016. He has had to roll with some heavyweight punches but has never come close to stepping out of the ring. What keeps him there is the feeling in his gut that keeps him obsessed by trying to win.

“I can only survive if I have that desire to win,” he explained. “If you only fight to win that means you have to forget your life first and foremost. You feel you have more chance to win if you concentrate every part of your energy on doing that. If you lose a day by not concentrating on that you feel guilty. The years and the years and the years teach you that every small detail can make you win or lose. Once you are convinced of that you cannot allow yourself to relax any more because you think, ‘Maybe I am making a mistake at the moment because I am not thinking about how I can win the next game.’ You become a winning animal. Somewhere you slowly forget your own life. I think any manager can only be happy if he wins. We all live desperate for it, and everybody will do everything to win. It’s not a regret, it’s just an explanation of how the life of a manager is.”

Whatever his critics make of him, he retains the full support of his club’s majority owner, Stan Kroenke, and the board. Their faith in him has not wavered. In Arsenal’s broader diaspora there is black, white and every shade of grey whenever there is discussion about Wenger’s ways. Some supporters frustrated by the ratio between high ticket prices and club honours vent their spleen and hold up banners. Others feel a sense of loyalty and affection for a man who has given a lot of himself to the club during his tenure. Many are stuck in the middle.

There is also a range of emotions among ex-players, men who in some cases grew up while playing in one of Wenger’s teams, and experienced defining moments of their careers in that time. It is curious that Wenger prefers to keep a professional distance with some of the greats who are starting out in coaching – Vieira, Henry, Bergkamp are among those who would have loved to return to work at the club but for whatever reason the invitations have not quite worked out. Others will never hear a word against him. Pirès is at the training ground most days. Ray Parlour tells stories with enormous warmth that show another side to the man who can often appear reserved in front of the post-match TV camera.

What the majority do not see is the personal side of Wenger, and the qualities that have kept him in the same job for so long. His keen intellect, his sense of trust in those around him (sometimes arguably too much trust), his dedication and his humour all make the man. He is very funny and has no problems laughing at himself. “He is such a clever man with such a knack at understanding people. But he could also be a walking disaster,” said Parlour. “He would do something accidentally every day.” He could get tangled up in the nets, drop the pudding off his plate without noticing, or join in a squad relaxation technique but lie with his legs up against a partition wall rather than a solid one and roll straight through it.

The Future (2016-?)

As The Bard wrote: “One man in his time plays many parts.” After 20 years there is no single perception of Wenger and his time.

We look today at the tall, wiry frame, sometimes bearing that strained expression when things are not going well, at others more urbane, with a ready wry smile and dry one-liner. In the current era of incessant managerial scrutiny, where millions of armchair managers give the impression of knowing better – something that occasionally provokes Wenger to dismiss the nerve of critics who cast judgment when they have never managed a single game – the pressure is relentless. But rest assured he goes home knowing that the biggest critic, the force who applies the harshest pressure, is the man in the mirror.

Because of the sheer weight of a 20-year marriage, it is natural to veer between periods of joy and frustration, lurch from moments of absolute faith to fierce doubt. Naturally most opinions are shaped by what is going on now. Today’s Wengerometer clearly does not hit the heights it has in the past. His Arsenal is a story in two acts. The first delivered wondrous success. The second has been complicated – maybe even so complicated, lasting a decade in itself, that many have forgotten how striking act one actually was.

The last act is yet to be written. His current deal expires at the end of this season and, as with all his other contracts, the only person who will decide if he signs another, walks away, moves upstairs, or tries something completely different is him. It is, as Wenger says, the club of his life. “What I like about Arsenal, and I am very proud of, is that the club is a mixture of respecting traditional values while not being scared to move forward,” he said. “I believe in the last 15 to 20 years you have all of that – fantastic periods, difficult periods – I stayed here for the respect I have for all that.”

Whatever happens and whenever it happens to end this collaboration between manager and club, Wenger is the last of his kind. The average timespan for a manager in England’s professional game is currently 13 months. We will not see a 20-year boss at elite level again.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion