Comment: Jose Mourinho shows Antonio Conte no subject is beneath him if you dare take him on

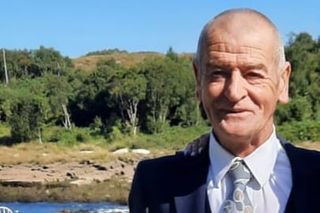

Jose Mourinho, left, and Antonio Conte have a long-standing feud

It felt inevitable that having spent most of Friday afternoon confronted with the footage of Antonio Conte diagnosing him with senile dementia, Jose Mourinho would respond in some fashion – the only question being the scale of his next managerial denunciation.

Mourinho’s most outrageous public remarks are generally perceived to be part of an overarching strategy, one as painstaking as the bespoke tactical performances he has dreamed up over the years to strangle opposition or win games. In fact, put Mourinho in front of a room of reporters and he is just as likely to respond in the moment with emotion than roll-out a carefully crafted plan refined over preceding days.

That he brought match-fixing, and its historical connection with Conte, onto the agenda fell somewhere between the two classic Mourinho responses. He left it until right to the end of a long monologue that seemed designed to put out the fire between the two men and then, at the last moment appeared to change his mind, perhaps reluctantly deciding that there was no alternative.

There are times when he is unmistakeably pre-meditated, such as the comments before the derby with Manchester City when Mourinho threw everything at Pep Guardiola, from his ribbon supporting the Catalan independence referendum to allegations of diving and tactical fouls. On Friday night he was vague enough about Conte and match-fixing allegations to suggest that he knew the severity of what he was doing and recognised that things could easily get out of hand.

His comment came at the end of a long lecture about how his remarks about touchline behaviour had been misconstrued, and that they had been used as a cover to question Conte because “probably the journalist wanted to say that but didn’t have the courage”. He was as conciliatory as he had ever been until with his final sentence he declared that “what has never happened to me and will never happen is to be suspended for match fixing.”

Given that he had earlier demanded everyone, especially journalists, own their views, Mourinho declined to do so when subsequently asked to clarify if he was talking about Conte’s match-fixing suspension over allegations from 2011. “Did he?” Mourinho responded when told Conte was suspended from the game for failing to report match-fixing. “Not me”.

As with all Mourinho attacks, there is unquestionably a kernel of truth to what he is saying. Conte was suspended by the Commissione Disciplinare della FIGC (the disciplinary commission of the Italian football association) for ten months, later reduced to four months on appeal for failing to report match-fixing in two games while he was in charge of Siena. As a consequence, in his next job as manager of Juventus he missed 15 Serie A games and six in the Champions League.

Then in May 2016 he was cleared of all charges against him in the Italian courts, where prosecutors were pushing for a six-month suspended jail sentence - by which time he was manager of Italy who were going into Euro 2016 that summer. The difference between being found guilty by a sporting body, but acquitted in the courts, is not impossible for the English game to comprehend, much the same having happened to John Terry over his use of racist language towards Anton Ferdinand in 2012.

What Mourinho has undoubtedly achieved has been the reigniting of an old scandal long since forgotten after Conte’s dazzling rookie season in the Premier League. He has also demonstrated to another rival that there is no place he is unprepared to go in order to undermine and damage anyone who challenges him as publically as Conte dared to do.

That is Mourinho’s way, a perpetual state of war with any who challenge him, or in whom he perceives weakness: Claudio Ranieri, Rafael Benitez, Arsene Wenger. It makes it all the more remarkable that for almost a decade he and Sir Alex Ferguson managed to dance around one another in that managerial bromance that, for all its courtesies just never felt right. The older man wary of Mourinho’s bite; Mourinho cautious of Ferguson’s immense appetite for bearing grudges.

Still it must be exhausting to maintain the aggression for so long and there are times when you suspect that even Mourinho is weary of it. There are few as infamous as his description of Wenger in February 2014 as a “specialist in failure”, an impulsive jab at the Arsenal manager yet within a few minutes of saying it Mourinho was already showing signs of regret. “I’ll be [perceived as] the impolite guy,” he said later speaking off camera to the newspapers, “the one who’s aggressive in his words.”

He seemed to be saying that this was his Pavlovian response, a reluctant instinct to annihilate the opposition in any argument. The career assassin who sees no other option but to attach the telescopic lens and squeeze the trigger one more time, knowing that one day it will be him on the receiving end. It does not change the fact that Mourinho has made the managerial rivalries much more bitter, more personal, more unpleasant, and so with grim symmetry the box office appeal of the Premier League has benefitted.

It lies at the heart of the Mourinho story, the former PE teacher who built a career from hard graft and rapid absorption of information; a nobody at 35, a world star at 41; the man who recalls his own father being sacked as a manager on Christmas Day. He will defend the reputation he has built at all costs and if it is the case that events escalate, that words get harder and allegations nastier, then that just happens to be an arms race he has decided he cannot afford to lose.