Loss of 'locals' dilutes passion of Liverpool-United battles as costly imports replace tradition

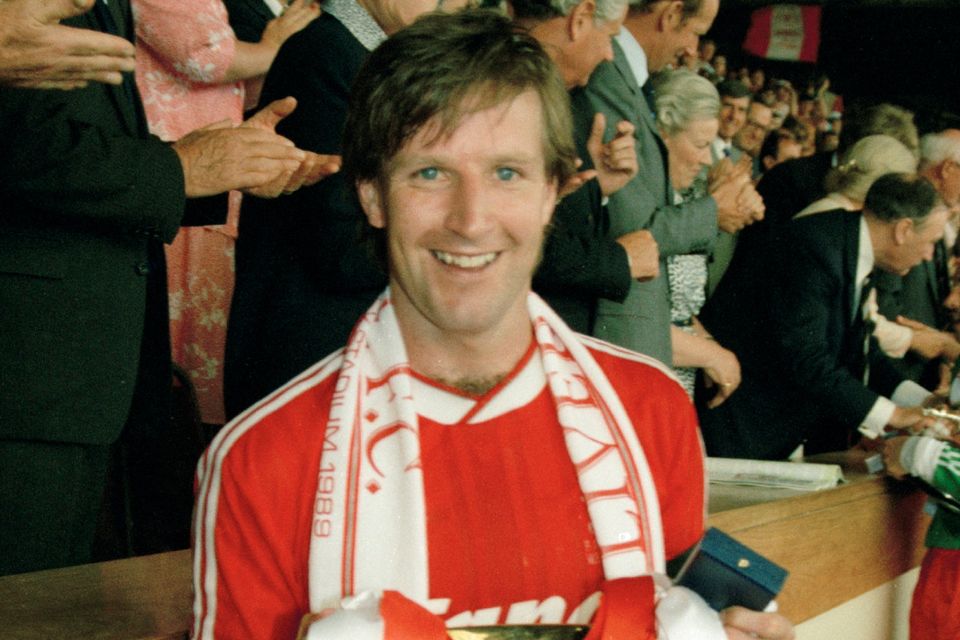

Ronnie Whelan. Photo: Getty

Compelling though it is likely to be, with Jurgen Klopp and Jose Mourinho on the touchline and Philippe Coutinho and Romelu Lukaku seeking to break open the action, who can deny some of the old allure will be absent when Manchester United arrive at Anfield tomorrow?

The clue yells from the top of that cast list. It is not about coaching or playing values. It is to do with the heart and the soul of a match which has shouted its passions down all the football years.

It is about identity and the fact that Klopp is German, Mourinho Portuguese, Coutinho Brazilian and Lukaku Belgian.

They are the most formidable performers, all of them, and in their different ways they do much to explain the perishing of the old football borders.

Certainly it would be an oddly unambitious Liverpool or United fan to fret over the colour of any of their passports. Still, you also have to admit, and mourn, the fact that something is missing, something which has always given Liverpool-United a sense not only of two great cities in fierce rivalry but the very flavour of these football islands.

No fixture ever celebrated more joyously the profusion of strength and talent and competitive character which stretched from Denis Law's Aberdeen to Roy Keane's Cork.

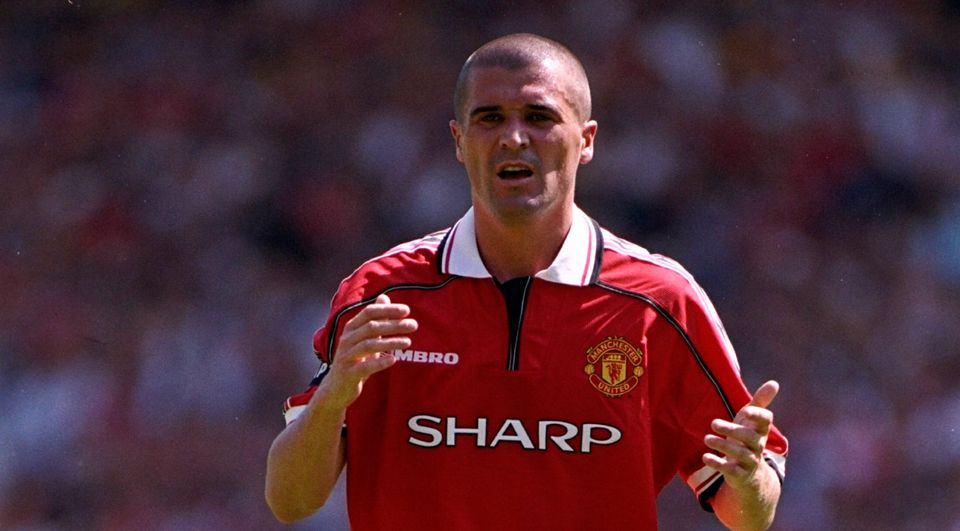

Roy Keane. Photo: Getty

It didn't matter whether you were English or Scottish, Welsh or Irish, there was always a point of special focus, a gifted native son in whom to feel pride.

Flick back the decades and there they all are. Johnny Carey, the master defender, smoking his pipe when the most sophisticated of battling was over on behalf of Matt Busby's United.

Jump 10 years and there is Johnny Giles bringing the boyish guile of the Dublin streets to United's first significant triumph since the Munich tragedy - the FA Cup of 1963 under the captaincy of Cork man Noel Cantwell.

Five years later Shay Brennan and Tony Dunne lifted the European Cup at Wembley, along with Georgie Best and one of England's ultimate heroes, Bobby Charlton.

And then down the road would come Paul McGrath, a world-class performer who survived Alex Ferguson's verdict that he was the bedevilled victim of the drink culture. And let's not forget Denis Irwin, who crowned superb service with a Champions League medal in 1999.

For Liverpool, the Irish footprint was hardly less distinct. Mark Lawrenson's Irish bloodline contributed to European Cup victory. Steve Heighway and Ray Houghton performed heroically.

Ronnie Whelan, for the best part of 15 years, was a Liverpool bulwark, always a leader, an enforcer of the strongest will - as he was on behalf of Ireland.

The Scots had their own hierarchy at Anfield, starting with Ian St John and Ronnie Yeats, of whom Shankly declared: "The man's a colossus".

Of course, there were great English stars nourished in the Anfield hothouse.

Roger Hunt was one of them. After a league game with United in 1964 he travelled with Bobby Charlton to meet the new manager of England, Alf Ramsey. They agreed that not much in football could be more challenging than the game they had just played at a feverish Anfield.

Tomorrow such stimulation belongs in another world to one inhabited by so many of the players from these islands.

There will be no long nourished heroes like Robbie Fowler or Stevie Gerrard, Best or Keane (left), Ian Rush or Ryan Giggs, Kenny Dalglish or Graeme Souness.

Maybe, for United, Marcus Rashford will steal a little of Lukaku's current glory and the English defenders Phil Jones and Chris Smalling might earn a credit or two.

An Englishman will lead Liverpool but Jordan Henderson will not, by running even a hundred miles and ceaselessly pointing in one obvious direction after another, conjure the memory of a Gerrard at his most explosive or Souness and Dalglish conjuring the best of their subtlety.

When Bob Paisley knew that he was certain to lose Kevin Keegan to Hamburg and the blossoming European football market, he had one thought.

"It was Kenny Dalglish," he revealed later. "He had everything I needed, everything Liverpool needed. He came from one great tradition to another."

But what do you do when great traditions die? In the case of Liverpool and United, and other Premier League clubs, you mostly trawl the goldfields of European and South American football.

One of the most impressive aspects of Ireland's fight into the World Cup play-offs in Cardiff was that it came so long after the football nation's rich contribution to the affairs of Liverpool and United had become forlornly historic. It was a triumph of will and persistence, a refusal to accept that because the tides of football had washed away the last generation of superior talent it was no reason to go meekly to defeat.

The poignancy comes in the fact that, if the past is the past, at Anfield tomorrow only a negligent memory would pass entirely on the glory of what this particular match had once come to mean.

It had represented the best of the islands' football prowess, the richest of its imagination and the hardest of its desire to win.

Once Shankly stood on the table of his office under the main stand at Anfield and spoke of the future of his emerging young team. He said, "It's going to go off like a great bloody bomb in the sky."

It may well be that there will be a detonation or two at Anfield tomorrow. But with the same force, forged by the same intense and passionate blood? Perhaps not. Maybe we'll need some kind of transfusion for that.